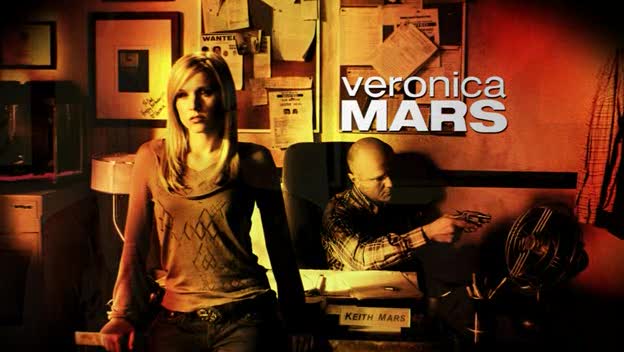

This piece was inspired by one of Anita Sarkeesian’s older videos, entitled “Why we need you Veronica Mars.” In this pre-“Tropes vs. Women in Video Games” video, Ms. Sarkeesian comments on the three-season TV series featuring Kristen Bell as the eponymous “tiny blond detective.” Drawing primarily from her particular school of feminism, she sets forth and discusses reasons why we need more characters and shows like Veronica Mars.

I’ve mentioned my fondness for mystery and detective fiction elsewhere, and I’m very familiar with Veronica Mars; I spent a whole summer binge-watching the show, and I was very excited when the movie came out in 2014. Neo-noir in style, almost Dashiell Hammett-like at times, and written with a deft, light touch that brought the characters and setting to vivid, gritty, California sun-soaked life, I think Veronica Mars is one of the best examples of contemporary detective fiction.

Just not for all the same reasons as Ms. Sarkeesian.

Now, I have nothing against Anita Sarkeesian– everything written online about her seems to portray her as either a much-needed voice in today’s conversation on culture or a charlatan and a con artist; I don’t know her personally, so I’d rather reserve judgment. And I have nothing against feminism, either. I believe in women’s rights for much the same reason that I believe in men’s rights: I believe in human rights, and in the radical notion that men and women are equal, though not equivalent. This won’t be a critique of her discussion, but I found Ms. Sarkeesian’s discussion somewhat limited; no doubt mine will be, too, but either way, I hope to show why we still need you, Veronica Mars.

Veronica as victim

“I need your help, Veronica.” It’s one of the most common lines throughout the series, spoken by someone calling her or cornering her after class or in the ladies’ room; it’s even said in the 2014 movie. With those five words, she once again steps into a world she never really leaves. A world of characters and events every bit as dubious and dangerous as the ones Holmes and Watson meet in Victorian England, and she manages to solve the case and get her homework done, too.

Veronica is like a court of last resort for the students of Neptune High and, later on, Hearst College. She deals with all these victims, finding solutions for their problems. What we have to remember is that she herself is a victim. Before the events of the TV series take place, her best friend Lilly Kane was murdered and her father, former sheriff Keith Mars, was kicked out of the Sheriff’s Office in an emergency recall election. She was drugged and raped at a party, and the sheriff to whom she reported it refused to believe her.

She is a victim, but she does not stay a victim: she gets up, dusts herself off and presses on. In her words,

Tragedy blows through your life like a tornado, uprooting everything, creating chaos. You wait for the dust to settle, and then you choose. You can live in the wreckage and pretend it’s still the mansion you remember. Or you can crawl from the rubble and slowly rebuild.

(S1E3, “Meet John Smith”)

Justice not for sale

Social inequality is a recurring theme, beginning in Season 1, where we’re introduced to the “09ers,” the rich inhabitants of Neptune, California (postal code 90909), characterized as a “town with no middle class,” ground zero when the class war comes.

In many of her cases, Veronica comes up against 09ers, and she outsmarts them, solving the case in the creative ways that Ms. Sarkeesian refers to in her video. The lesson is that justice isn’t a product that goes to the highest bidder; it isn’t something that the 09ers can buy. Something we have to remember every time we hear about the most shocking miscarriages of justice brought about by deep pockets. “Justice on the side of the highest bidder” is not justice at all.

Friends, family, partners in crime

In her video, Ms. Sarkeesian mentions two important characters: Veronica’s father and mentor, Keith Mars, and her friend, the tech-savvy Mac Mackenzie, who ends up working at Mars Investigations in the novels set after the events of the series and movie (and which, unfortunately, I haven’t read yet, but I’ll get around to reading The Thousand-Dollar Tan Line soon. No spoilers! 🙂 ).

She only appears as a minor character, but Veronica also has Lianne, her alcoholic mother, who left them after Keith was voted out of office. Veronica uses up her college funds to send her to rehab– an arrangement that doesn’t turn out well, and puts her future in jeopardy.

I found the omission of Wallace Fennel a glaring omission on Ms. Sarkeesian’s part. Wallace is roped into Veronica’s cases a few times, and he is portrayed as a loyal, foul-weather friend.

Keith, Mac, and Wallace show us the importance of our friends and family. On the other hand, Lianne shows us that sometimes, the people closest to us end up hurting us. That doesn’t make them evil; it just means they’re not perfect.

Veronica Mars is a hero

That’s right, she isn’t just a marshmallow. Veronica Mars is a hero.

We tend to form cults around our heroes. In places such as China or North Korea, cults around heroes tend to take a rather scary turn, with iconography and, sometimes, “hagiography” almost comparable to Catholic saints.

We sometimes forget that our heroes aren’t perfect, aren’t infallible or impeccable. Veronica is cynical– not without cause– at times indecisive, makes the wrong decisions, and sometimes it appears as though she doesn’t appreciate Wallace’s help. She isn’t perfect, but then again, who is?

She might not be perfect, but in spite of that, she always sets things right.

In the end, who is Veronica Mars?

She is a friend, a daughter, a detective, an avenging angel, a flawed and human character. She is a hero, and we could always use more heroes.

Aletheia Observer, signing out. Be careful out there! 🙂

– A.O.